As you probably have heard by now, Clayton Christensen — renown author, professor, and consultant on the topic of disruptive innovation — passed away late last week. I didn’t know him personally, but I had the privilege of meeting him on several occasions. And the ideas he shared in his writing and presentations have had a significant impact on my life.

My first encounter with Clay’s concept of disruptive innovation was in 1994.

At the time, I was the 23-year-old CEO of the world’s largest BBS software company. We had over 20,000 customers running business and entertainment online systems on our platform, The Major BBS, from hobbyist operators to Fortune 500 companies. Our software was pretty advanced, essentially letting anyone run their own miniature CompuServe or America OnLine service on a PC. We were on the top of the world. Or so I thought.

At the time, one of my product leaders sat me down to walk me through a number of websites using an early version of the Netscape browser. He was trying to convince me that the web was the future, and that it posed an existential risk to our business.

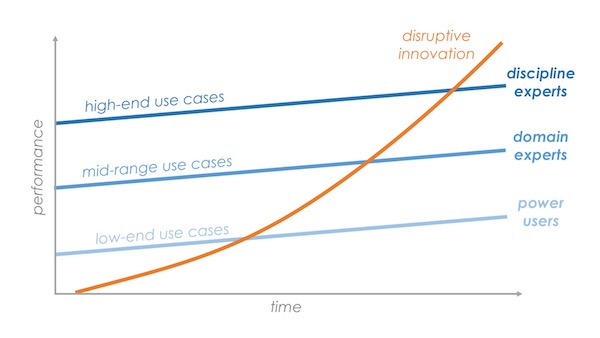

I didn’t know it at the time, but I made the very mistake Christensen would warn companies of in The Innovator’s Dilemma: underestimating a disruptive innovation for the low-end use cases it initially served. I looked at how laughably “weak” the features of those early websites were in comparison to our sophisticated BBS software and blew it off. “Yeah, yeah, so you can publish slow, static pages with text and images. That’s never going to threaten the advanced interactive services that customers rely on our software for.”

You can guess how that story ended.

Within two years, our company was sold at a fire sale price. Within three years, BBSes were all but extinct. All those advanced use cases that I thought protected us from being disrupted by the web? Eventually websites did all of that and much, much more.

It was a searingly painful lesson.

Shortly afterwards, Christensen published The Innovator’s Dilemma. Reading it triggered a kind of post-traumatic stress for me. I found myself reliving the train wreck of my strategic blunder in his simple but profound illustrations of disruptive innovation dynamics. The corner we had backed ourselves into… Was. So. Clear.

From that point forward, the wisdom of his model was forever imprinted on my brain. Working in marketing and technology for the past 20 years has been nothing but a wild maelstrom of disruptive technologies, so I’ve certainly had plenty of opportunities to make good use of it.

While I’ve made plenty of other mistakes, being caught unaware by “disruption from below” has been one I’ve been far less susceptible to. When my previous company, ion interactive, found our landing page platform being commoditized from below, we successfully pivoted to a whole new market of interactive content (“marketing apps”).

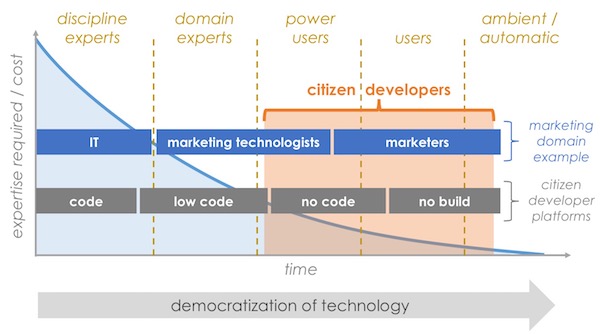

One of the reasons that I’m so bullish on “citizen technologists” — citizen developers, citizen analysts, citizen integrators, etc. using low-code and no-code tools to do things that used to require specialized, technical experts — is that it’s a perfect example of Christensen’s model playing out on a grand scale.

See: Now every marketer is an app developer — even if they don’t know it.

I have been banging on this no-code drum since 2018, and the objections I’ve heard are taken almost word-for-word from Christensen’s script of the soon-to-be-disrupted: “Those aren’t real apps.” “That’s fine for those simple use cases, but it can’t serve our pro-level needs.”

Each year, the use cases covered by no-code solutions slide up the performance curve. Slowly, the voices dismissing its potential are being matched by voices celebrating its power. Mark my words: within 5 years, the no-code revolution will be looked back on as a quintessential case study of Christensen’s disruptive innovation theory.

Ignore it now at your own peril.

There’s much more I’ve learned from Christensen over the years. His jobs-to-be-done model for understanding product-market fit and effective marketing — colloquially called “milkshake marketing” from the initial research project for a fast-food company that catalyzed the theory — is, hands-down, the best strategic marketing framework I know. If you haven’t read his book, Competing Against Luck, which covers it in great detail, run — don’t walk — to get a copy.

But the most personal memory I have of him is when I met him in the fall of 2005. At the time, I was attending an MBA program at MIT. A group of us who were Christensen fan-boys and fan-girls invited him to come talk to us — and he accepted. He didn’t teach at MIT, but up the river at Harvard, and with his consulting practice was immensely busy with epic engagements such as I can only imagine. Yet he found the time to come talk with us for a couple of hours, asking nothing in return.

I was the one assigned to greet him and navigate him through the MIT parking lot. It was under construction at the time, and a total mess. He ended up far away from our building, trying to avoid being towed, and we had to schlep through cold, windy Boston rain. If he had expressed even an ounce of annoyance to me, I would have completely understood. But on the contrary, he was the epitome of graciousness.

The talk he gave us that day wasn’t about disruptive innovation. It was about the themes he would later write in the book How Will You Measure Your Life? — about not only making sure that we didn’t sacrifice our values for “business,” but that we fundamentally built those values into the pursuits of our lives. He left us completely awed in silence.

Thank you, Clay. I’m grateful to have learned so much from you. Rest in peace.

The post Thank you, Clay Christensen, for everything you taught me about disruptive innovation and more appeared first on Chief Marketing Technologist.

from Chief Marketing Technologist https://ift.tt/2TTdO30

via IFTTT

Comments

Post a Comment